Muhammad Ali, the three-time world heavyweight boxing champion who helped define his turbulent times as the most charismatic and controversial sports figure of the 20th century, died on Friday in a Phoenix-area hospital. He was 74.

His death was confirmed by Bob Gunnell, a family spokesman.

Ali was the most thrilling if not the best heavyweight ever, carrying into the ring a physically lyrical, unorthodox boxing style that fused speed, agility and power more seamlessly than that of any fighter before him.

But he was more than the sum of his athletic gifts. An agile mind, a buoyant personality, a brash self-confidence and an evolving set of personal convictions fostered a magnetism that the ring alone could not contain. He entertained as much with his mouth as with his fists, narrating his life with a patter of inventive doggerel. (“Me! Wheeeeee!”)

Ali was as polarizing a superstar as the sports world has ever produced — both admired and vilified in the 1960s and ’70s for his religious, political and social stances. His refusal to be drafted during the Vietnam War, his rejection of racial integration at the height of the civil rights movement, his conversion from Christianity to Islam and the changing of his “slave” name, Cassius Clay, to one bestowed by the separatist black sect he joined, the Lost-Found Nation of Islam, were perceived as serious threats by the conservative establishment and noble acts of defiance by the liberal opposition.

Loved or hated, he remained for 50 years one of the most recognizable people on the planet.

In later life Ali became something of a secular saint, a legend in soft focus. He was respected for having sacrificed more than three years of his boxing prime and untold millions of dollars for his antiwar principles after being banished from the ring; he was extolled for his un-self-conscious gallantry in the face of incurable illness, and he was beloved for his accommodating sweetness in public.

In 1996, he was trembling and nearly mute as he lit the Olympic caldron in Atlanta.

That passive image was far removed from the exuberant, talkative, vainglorious 22-year-old who bounded out of Louisville, Ky., and onto the world stage in 1964 with an upset victory over Sonny Liston to become the world champion. The press called him the Louisville Lip. He called himself the Greatest.

Ali also proved to be a shape-shifter — a public figure who kept reinventing his persona.

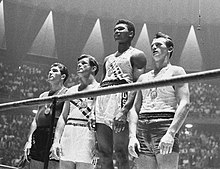

As a bubbly teenage gold medalist at the 1960 Olympics in Rome, he parroted America’s Cold War line, lecturing a Soviet reporter about the superiority of the United States. But he became a critic of his country and a government target in 1966 with his declaration “I ain’t got nothing against them Vietcong.”

“He lived a lot of lives for a lot of people,” said the comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory. “He was able to tell white folks for us to go to hell.”

But Ali had his hypocrisies, or at least inconsistencies. How could he consider himself a “race man” yet mock the skin color, hair and features of other African-Americans, most notably Joe Frazier, his rival and opponent in three classic matches? Ali called him “the gorilla,” and long afterward Frazier continued to express hurt and bitterness.

If there was a supertitle to Ali’s operatic life, it was this: “I don’t have to be who you want me to be; I’m free to be who I want.” He made that statement the morning after he won his first heavyweight title. It informed every aspect of his life, including the way he boxed.

The traditionalist fight crowd was appalled by his style; he kept his hands too low, the critics said, and instead of allowing punches to “slip” past his head by bobbing and weaving, he leaned back from them.

Eventually his approach prevailed. Over 21 years, he won 56 fights and lost five. His Ali Shuffle may have been pure showboating, but the “rope-a-dope” — in which he rested on the ring’s ropes and let an opponent punch himself out — was the stratagem that won the Rumble in the Jungle against George Foreman in 1974, the fight in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) in which he regained his title.

His personal life was paradoxical. Ali belonged to a sect that emphasized strong families, a subject on which he lectured, yet he had dalliances as casual as autograph sessions. A brief first marriage to Sonji Roi ended in divorce after she refused to dress and behave as a proper Nation wife. (She died in 2005.) While married to Belinda Boyd, his second wife, Ali traveled openly with Veronica Porche, whom he later married. That marriage, too, ended in divorce.

Ali was politically and socially idiosyncratic as well. After the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the television interviewer David Frost asked him if he considered Al Qaeda and the Taliban evil. He replied that terrorism was wrong but that he had to “dodge questions like that” because “I have people who love me.” He said he had “businesses around the country” and an image to consider.

As a spokesman for the Muhammad Ali Center, a museum dedicated to “respect, hope and understanding,” which opened in his hometown, Louisville, in 2005, he was known to interrupt a fund-raising meeting with an ethnic joke. In one he said: “If a black man, a Mexican and a Puerto Rican are sitting in the back of a car, who’s driving? Give up? The po-lice.”

But Ali had generated so much good will by then that there was little he could say or do that would change the public’s perception of him.

“We forgive Muhammad Ali his excesses,” an Ali biographer, Dave Kindred, wrote, “because we see in him the child in us, and if he is foolish or cruel, if he is arrogant, if he is outrageously in love with his reflection, we forgive him because we no more can condemn him than condemn a rainbow for dissolving into the dark. Rainbows are born of thunderstorms, and Muhammad Ali is both.”

Ambition at an Early Age

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. was born in Louisville on Jan. 17, 1942, into a family of strivers that included teachers, musicians and craftsmen. Some of them traced their ancestry to Henry Clay, the 19th-century representative, senator and secretary of state, and his cousin Cassius Marcellus Clay, a noted abolitionist.

Ali’s mother, Odessa, was a cook and a house cleaner, his father a sign painter and a church muralist who blamed discrimination for his failure to become a recognized artist. Violent and often drunk, Clay Sr. filled the heads of Cassius and his younger brother, Rudolph (later Rahman Ali), with the teachings of the 20th-century black separatist Marcus Garvey and a refrain that would become Ali’s — “I am the greatest.”

Beyond his father’s teachings, Ali traced his racial and political identity to the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, a black 14-year-old from Chicago who was believed to have flirted with a white woman on a visit to Mississippi. Clay was about the same age as Till, and the photographs of the brutalized dead youth haunted him, he said.

Cassius started to box at 12, after his new $60 red Schwinn bicycle was stolen off a downtown street. He reported the theft to Joe Martin, a police officer who ran a boxing gym. When Cassius boasted what he would do to the thief when he caught him, Martin suggested that he first learn how to punch properly.

Cassius was quick, dedicated and gifted at publicizing a youth boxing show, “Tomorrow’s Champions,” on local television. He was soon its star.

For all his ambition and willingness to work hard, education — public and segregated — eluded him. The only subjects in which he received satisfactory grades were art and gym, his high school reported years later. Already an amateur boxing champion, he graduated 376th in a class of 391. He was never taught to read properly; years later he confided that he had never read a book, neither the ones on which he collaborated nor even the Quran, although he said he had reread certain passages dozens of times. He memorized his poems and speeches, laboriously printing them out over and over.

Muhammad Ali’s Words Stung Like a Bee, Too

Outside the boxing ring, Ali fought his battles with his mouth.

In boxing he found boundaries, discipline and stable guidance. Martin, who was white, trained him for six years, although historical revisionism later gave more credit to Fred Stoner, a black trainer in the Smoketown neighborhood. It was Martin who persuaded Clay to “gamble your life” and go to Rome with the 1960 Olympic team despite his almost pathological fear of flying.

Clay won the Olympic light-heavyweight title and came home a professional contender. In Rome, Clay was everything the sports diplomats could have hoped for — a handsome, charismatic and black glad-hander. When a Russian reporter asked him about racial prejudice, Clay ordered him to “tell your readers we got qualified people working on that, and I’m not worried about the outcome.”

“To me, the U.S.A. is still the best country in the world, counting yours,” he added. “It may be hard to get something to eat sometimes, but anyhow I ain’t fighting alligators and living in a mud hut.”

Ali would later cringe at that quotation, especially when journalists harked back to it as proof that a merry man-child had been misguided into becoming a hateful militant.

Olympian, Conscientious Objector and Heavyweight Champion

How The New York Times covered the career of Muhammad Ali.

FROM THE ARCHIVE | SEPT. 7, 1920

Cassius Clay Wins an Olympic Gold Medal

Muhammad Ali's first mention in The New York Times was a piece on winners at the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome. He won the gold medal in the light heavyweight boxing division.

The New York Times

See full article in TimesMachine

1 of 10

Of course, after the Rome Games, few journalists followed Clay home to Louisville, where he was publicly referred to as “the Olympic nigger” and denied service at many downtown restaurants. After one such rejection, the story goes, he hurled his gold medal into the Ohio River. But Clay, and later Ali, gave different accounts of that act, and according to Thomas Hauser, author of the oral history “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times,” Clay had simply lost the medal.

Clay turned professional by signing a six-year contract with 11 local white millionaires. (“They got the complexions and connections to give me good directions,” he said.) The so-called Louisville Sponsoring Group supported him while he was groomed by Angelo Dundee, a top trainer, in Miami.

At a mosque there, Clay was introduced to the Nation of Islam, known to the news media as “Black Muslims.” Elijah Muhammad, the group’s leader, taught that white people were devils genetically created by an evil scientist. On Allah’s chosen day of retribution, the Mother of Planes would bomb all but the righteous, and the righteous would be spirited away.

Years later, after leaving the group and converting to orthodox Islam, Ali gave the Nation of Islam credit for offering African-Americans a black-is-beautiful message at a time of low self-esteem and persecution. “Color doesn’t make a man a devil,” he said. “It’s the heart and soul and mind that count. What’s on the outside is only decoration.”

Title and Transformation

Clay enjoyed early success against prudently chosen opponents. His outrageous predictions, usually in rhyme — “This is no jive, Cooper will go in five” — put off many older sportswriters, especially since most of the predictions came true. (The Englishman Henry Cooper did go down in the fifth round at Wembley Stadium in 1963, after he had staggered Clay in the fourth.) The reporters’ beau ideal of a boxer was the laconic Joe Louis. But they still wrote about Clay. Younger sportswriters, raised in an age of Andy Warhol, happenings and the “put on,” were delighted by the hype and by Clay’s friendly accessibility.

In 1963, at 21, after only 15 professional fights, he was on the cover of Time magazine. The winking quality of the prose — “Cassius Clay is Hercules, struggling through the twelve labors. He is Jason, chasing the Golden Fleece” — reinforced the assumption that he was just another boxer being sacrificed to the box office’s lust for fresh meat. It was feared he would be seriously injured by the baleful slugger Liston, a 7-to-1 betting favorite to retain his title in Miami Beach, Fla., on Feb. 25, 1964.

But Clay was joyously comic. Encouraged by his assistant trainer and “spiritual adviser,” Drew Brown, known as Bundini, Clay mocked Liston as the “big ugly bear” and chanted a battle cry: “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee, rumble, young man, rumble.”

The Beatles, on their first American tour, were in town and showed up for a photo op at Clay’s training gym. Malcolm X, a leading minister for the Nation of Islam and a worrisome presence to many white Americans, was there, too, with his family members as guests of Clay, whom they saw as a big brother.

To the shock of the crowd, Clay, taller and broader than Liston at 6 feet 3 inches and 210 pounds and much faster, took immediate control of the fight. He danced away from Liston’s vaunted left hook and peppered his face with jabs, opening a cut over his left eye. Clay was in trouble only once. Just before the start of the fifth round, his eyes began to sting. It was liniment, but he suspected poison. Dundee had to push him into the ring. Two rounds later, Liston, slumped on his stool, his left arm hanging uselessly, gave up. He had torn muscles swinging at Clay in vain.

Clay, the new champion, capered along the ring apron, shouting at the press: “Eat your words! I shook up the world! I’m king of the world!”

The next morning, a calm Clay affirmed his rumored membership in the Nation of Islam. He would be Cassius X. (A few weeks later he became Muhammad Ali, which he said meant “Worthy of all praise most high.”) That day he harangued his audience with a preview of what would, over the next few years, become a series of longer and more detailed lectures about religion and race. This one was about, as he put it, “staying with your own kind.”

“In the jungle, lions are with lions and tigers with tigers,” he said. “I don’t want to go where I’m not wanted.”

The only prominent leader to send Ali a telegram of congratulations was the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“I remember when Ali joined the Nation of Islam,” Julian Bond, the civil rights activist and politician, once said. “The act of joining was not something many of us particularly liked. But the notion he’d do it — that he’d jump out there, join this group that was so despised by mainstream America, and be proud of it — sent a little thrill through you.”

The thrills gave way to darker thoughts. After Malcolm X left the Nation and was assassinated on Feb. 21, 1965, by members of the group, there was talk that Ali had been tacitly complicit. Jack Newfield, a political journalist with an interest in boxing, wrote, “If Ali, as the new heavyweight champion, had remained loyal to his mentor, and continued to lend his public support to Malcolm, history might have gone in a different direction.”Refusing to Be Drafted

On Feb. 17, 1966, a day already roiled by the Senate’s televised hearings on the war in Vietnam, Ali learned that he had been reclassified 1A by his Louisville selective service board. He had originally been disqualified by a substandard score on a mental aptitude test. But a subsequent lowering of criteria made him eligible to go to war. The timing, however, was suspicious to some; the contract with the Louisville millionaires had run out, and Nation members were taking over as Ali’s managers and promoters.

“Why me?” Ali said when reporters swarmed around his rented Miami cottage to ask about his new draft status. “I buy a lot of bullets, at least three jet bombers a year, and pay the salary of 50,000 fighting men with the money they take from me after my fights.”

But as the reporters continued to press him with questions about the war, the geography of Asia and his thoughts about killing Vietcong, he snapped, “I ain’t got nothing against them Vietcong.”

The remark was front-page news around the world. In America, the news media’s response was mostly unfavorable, if not hostile. The sports columnist Red Smith of The New York Herald Tribune wrote, “Squealing over the possibility that the military may call him up, Cassius makes himself as sorry a spectacle as those unwashed punks who picket and demonstrate against the war.”

Most of the press refused to refer to Ali by his new name. When two black contenders, Floyd Patterson and Ernie Terrell, insisted on calling him Cassius Clay, Ali taunted them in the ring as he delivered savage beatings.

On April 28, 1967, Ali refused to be drafted and requested conscientious-objector status. He was immediately stripped of his title by boxing commissions around the country. Several months later he was convicted of draft evasion, a verdict he appealed. He did not fight again until he was almost 29, losing three and a half years of his athletic prime.

They were years of personal and intellectual growth, however, as Ali supported himself on the college lecture circuit, offering medleys of Muslim dogma and boxing verse. In the question-and-answer sessions that followed, Ali was forced to explain his religion, his Vietnam stand and his opposition (unpopular on most campuses) to marijuana and interracial dating. Now the “onliest boxer in history that people asked questions like a senator” developed coherent answers.

During his exile from the ring, Ali starred in a short-lived Broadway musical, “Big Time Buck White,” one of several commercial ventures. There was a fast-food chain called Champburger and a mock movie fight with the popular former champion Rocky Marciano in which Ali outboxed the slugger until being knocked out himself in the final round. The broadcaster Howard Cosell, one of Ali’s most steadfast supporters in the news media, was responsible for keeping him on television, both as an interview subject and as a commentator on boxing matches.

As Ali’s draft-evasion case made its way to the United States Supreme Court, he returned to the ring on Oct. 26, 1970, through the efforts of black politicians in Atlanta. The fight, which ended with a quick knockout of the white contender Jerry Quarry, was only a tuneup for Ali’s anticipated showdown with Frazier, the new champion. But it was a night of glamour and history as Coretta Scott King, Bill Cosby, Diana Ross, the Rev. Jesse Jackson and Sidney Poitier turned out to honor Ali. The Rev. Ralph Abernathy presented him with the annual Dr. King award, calling him “the March on Washington all in two fists.”

“The Fight,” as the Madison Square Garden bout with Frazier on March 8, 1971, was billed, lived up to expectations as an epic match. With Norman Mailer ringside taking notes for a book and Frank Sinatra shooting pictures for Life magazine, Ali stood toe to toe with Frazier and slugged it out as if determined to prove that he had “heart,” that he could stand up to punishment. Frazier won a 15-round decision. Both men suffered noticeable physical damage.

To Ali’s boosters, the money he had lost standing up for his principles and the beating he had taken from Frazier proved his sincerity. To his critics, the bloody redemption meant he had finally grown up. The Supreme Court also took a positive view. On June 28, 1971, it unanimously reversed a lower court decision and granted Ali his conscientious-objector status.

Resurgence and Decline

It was assumed now that Ali’s time had passed and that he would become a high-grade “opponent,” the fighter to beat for those establishing themselves. But his time had returned. Although he was slower, his artistry was even more refined. “He didn’t have fights,” wrote Jim Murray of The Los Angeles Times, “he gave recitals.”

He won 13 of his next 14 fights, including a rematch with Frazier, who had lost his title to George Foreman, a bigger, more frightening version of Liston.

Ali was the underdog, smaller and seven years older than Foreman, when they met on Oct. 30, 1974, in Zaire, then ruled by Mobutu Sese Seko. Each fighter was guaranteed $5 million, an extraordinary sum at the time. The fight also launched the career of the promoter Don King and was the subject of Leon Gast’s documentary “When We Were Kings,” which was released more than 20 years later. (Ali attended a special screening, along with hip-hop performances, at Radio City Music Hall.) The film won a 1997 Academy Award.

Ali reveled in the African setting, repeating an aphorism he had heard from Brown, his assistant trainer: “The world is a black shirt with a few white buttons.”

As the fight progressed, the crowd chanted, “Ali, bomaye!” (“Ali, kill him!”), first out of concern as Ali leaned against the ropes and absorbed Foreman’s sledgehammer blows on his arms and shoulders, and then in mounting excitement as Foreman wore himself out. In the eighth round, in a blur of punches, Ali knocked out Foreman to regain the title. He leaned down to reporters and said, “What did I tell you?”

On Dec. 10, 1974, Ali was invited to the White House for the first time, by President Gerald R. Ford, an occasion that signified not only a turning point in the country’s embrace of Ali but also a return of the Lip. Ali told the president, “You made a big mistake letting me come because now I’m going after your job.”

Ali successfully defended his title 10 times over the next three years, at increasing physical cost. He knocked out Frazier in their third match, the so-called Thrilla in Manila in 1975, but the punishment of their 14 rounds, Ali said, felt close to dying.

In 1978 he lost and then regained his title in fights with Leon Spinks. Ali’s longtime ring doctor, Ferdie Pacheco, urged him to quit, noting the slowing of his reflexes and the slurring of his speech as symptoms of damage. Ali refused. In 1980, he was battered in a loss to the champion Larry Holmes. A year later, he fought for the last time, losing to the journeyman Trevor Berbick in the Bahamas.

Ali was soon told that he had Parkinson’s syndrome. Several doctors have speculated that it was brought on by too many punches to the head. The diagnosis was later changed to Parkinson’s disease, according to his wife, Lonnie. She said it had been brought on by Ali’s exposure to pesticides and other toxic chemicals at his training camp in Deer Lake, Pa.

A Champion Is Celebrated

After retiring from the ring, Ali made speeches emphasizing spirituality, peace and tolerance, and undertook quasi-diplomatic missions to Africa and Iraq. Even as he lost mobility and speech, he traveled often from his home in Berrien Springs, Mich. Product and corporate endorsements brought him closer to the “show me the money” sensibilities of Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods, the heirs to his global celebrity.

In 1999, Ali became the first boxer on a Wheaties box. On Dec. 31 that year, he rang out the millennium at the New York Stock Exchange. In 2003, a $7,500 art book celebrating his life was published. His life was the subject of a television movie and a feature film directed by Michael Mann, with Will Smith as Ali. (Both productions sanitized his early religious and political viewpoints.) The same licensing firm that owned most of Elvis Presley’s image purchased rights to Ali’s.

Thomas Hauser, his biographer, decried the new “commercialism” surrounding Ali and “the rounding off the rough edges of his journey.” In a book of essays published in 2005, “The Lost Legacy of Muhammad Ali,” Hauser wrote, “We should cherish the memory of Ali as a warrior and as a gleaming symbol of defiance against an unjust social order when he was young.”

In 2005, calling him the greatest boxer of all time, President George W. Bush presented the Medal of Freedom to Ali in a White House ceremony.

In recent years, Parkinson’s disease and spinal stenosis, which required surgery, limited Ali’s mobility and ability to communicate. He spent most of his time at his home in Paradise Valley, Ariz., often watching Western movies and old black-and-white TV shows. He ventured out mostly for physical therapy, movies and concerts. He rarely did TV interviews, his wife said, because he no longer liked the way he looked on camera.

“But he loved the adoration of crowds,” she said. “Even though he became vulnerable in ways he couldn’t control, he never lost his childlike innocence, his sunny, positive nature. Jokes and pranks and magic tricks. He wanted to entertain people, to make them happy.”

*****

A Look Back at the Greatest

John Rooney/Associated Press

At the end, the mischief was still in his eyes. Even the pall of Parkinson’s disease never took that away, but for too many years before his death,Muhammad Ali was not the Muhammad Ali you wanted to remember. Instead of shouting, “I am the greatest,” he whispered. Instead of whirling in his white boxing shoes with red tassels, he shuffled. And instead of that wonderful face lighting up when he spoke, he wore a cheerless mask.

Whenever people asked you about him lately, you always preferred to tell them what he was like in all those years when you covered 32 of his fights, what he was like when he really was Muhammad Ali.

To go back to the beginning, you told them what he was like the first time you met him, when he was Cassius Clay in the days before he won a disputed decision over Doug Jones in 1963 at the old Madison Square Garden and you were in his Midtown hotel room.

“Stand up and put your hands up like a boxer,” he ordered, circling and then flicking his left jab inches from your chin as you blinked. “Pop, pop, pop. Ain’t never been a heavyweight fast as me.”

Sonny Liston learned that, twice. But for all of Ali’s flash as the new champion, you learned that he could be cruel when he tortured Floyd Patterson and taunted Ernie Terrell. And in 1967, with Ali surrounded by Black Muslim bodyguards in black suits and black bow ties, you listened as he sat in the basement of the Garden after a workout before his title defense against Zora Folley and implied that he would go to prison rather than obey his Army induction order during the Vietnam War.

“For my beliefs,” he said.

At a Houston induction center, Ali did not take the symbolic “step forward” in compliance with the military draft. Stripped of the heavyweight championship by boxing politicians and convicted of refusing Army induction, he began a three-and-a-half-year exile. By the time he fought Joe Frazier in their March 8, 1971, spectacle at the new Garden, he remained an unpatriotic villain to some, a hero to others for standing up to the government. The morning after his first loss and an embarrassing knockdown, his jaw was still swollen, and he winced whenever he moved on the bed in his hotel room.

“When a man gets me going, that’s a punch, and when a man drops me, that’s a hell of a punch,” he said, referring to Frazier’s left hook in the 15th round. “I didn’t give the fight to him. He earned it.”

When the Supreme Court reversed his 1967 conviction for refusing Army induction, he was free. But it took three years and a 12-round decision over Frazier before he got another shot at the title, then held by the undefeated knockout puncher George Foreman, in Kinshasa, Zaire. In a 1974 bout that began there at 4 o’clock in the morning to accommodate closed-circuit theater television in the United States, you heard his 60,000 worshipers in a soccer stadium chanting, “Ali, bomaye,” meaning “Ali, kill him.”

In the eighth round, Ali, who had covered up with his back against the ropes while Foreman punched himself out, threw a right hand that spun Foreman onto the canvas. KO 8.

“The surprise is that I did not dance,” you heard him say later outside his villa along the Congo River. “For weeks I kept hollering, ‘Be ready to dance,’ but I didn’t dance. That was the surprise. That was the trick. I told him, ‘You’re the champ, George, and I’m eatin’ you up.’ Don’t ever match no bull against a master boxer. The bull is stronger, but the matador’s smarter.”

As champion for the second time, Ali was suddenly more popular than ever. And he was having more fun than ever.

After he and Joe Bugner selected the gloves for their 1975 title bout in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, you noticed Ali staring at the commission official who put the gloves in separate boxes, then sealed the boxes with wax from a burning candle.

“Where are you taking the gloves?” he asked.

“We’re putting them in jail,” the official explained. “To make sure nobody tampers with them, we’re putting the gloves in a safe in jail.”

“The gloves are going to jail,” he said, his eyes wide. “The gloves ain’t done nothin’ — yet.”

Three months later, in what Ali called the Thrilla in Manila, he survived a brutal third fight with Frazier when Frazier’s trainer, Eddie Futch, would not let him answer the bell for the 15th round. Futch explained that Frazier, his left eye closed, could not see Ali’s right hand coming. Minutes later, Frazier was in the interview area, talking about what happened, and he later boogied at his postfight party.

Ali needed nearly an hour to face the news media, and when asked what the fight had been like, you heard him say, “Next to death.” At his postfight party, he sat stiffly and silently.

You’re not a doctor, but you have often thought that if Ali had retired after Manila, maybe Parkinson’s disease would not have hit him harder than even Joe Frazier ever had.

It wasn’t so much that Ali had too many fights after Manila; maybe it was that he had too many hard rounds with Jimmy Young, Ken Norton, Earnie Shavers, Leon Spinks (losing the title, then gaining it for the third time), Larry Holmes and Trevor Berbick. When he finally retired, you stopped by a Miami gym where, at 40, he was working out before an exhibition tour of Saudi Arabia, India and Pakistan. That’s when you noticed he was slurring his words.

“Ihad aphysical inLosAngeles forthistour,” he mumbled, his words clinging together as cobwebs of dust do. “I’mperfect.”

He was far from perfect, of course. And month by month and year by year, his speech slurred more and more. Whenever you saw him and you watched him playfully pretend to throw a punch or do his magic tricks, you could see the twinkle in his eyes and you knew the mischief was still there. But he was not the Muhammad Ali you wanted to remember. And he never would be.

*****

I was not yet a teenager when I wandered into the living room of our rent-controlled apartment on the Upper West Side. I saw my parents sitting silently by our black-and-white television, listening as a young black boxer,Muhammad Ali, talked.

He was saying he would not serve in the Army and he would not fight those Vietcong.

“My conscience won’t let me go and shoot them,” Ali said in that rat-a-tat-tat stream-of-consciousness style of his. “They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me.”

“How can I shoot those poor people?” he added. “Just take me to jail.”

Just take me to jail. Those words registered as astonishing. Here was this great, sexy fighter on the cusp of fame and fortune, a physically pretty man who recited doggerel and who graced the covers of magazines. And he was willing to march off to prison to protest an unjust war.

We celebrate athletic courage. Watch a hoopster hit a spinning, fall-away jumper in the last seconds, see a center fielder race toward a fence heedless of the possible injury, applaud a fullback who catapults into the end zone, and we talk of courage.

Such feats are athletic and wonderful and memorable. Courage is being 24 years old and risking all, the anger of newspaper and television reporters and millions of white Americans who see you as a public enemy, to say no to a war.

Channing Frye, a tall and lithe Cleveland Cavalier, stepped onto the practice court in Oakland for an interview on the intricacies of the N.B.A. finals. He’s thoughtful on his chosen vocation; first, though, he spoke of the septuagenarian Ali.

“He just gave the black community a lot of courage and changed our mind-set: ‘Hey, you can be a superstar and not be quiet,’ ” Frye said. “You can voice your opinion and be controversial and still be a champion.”

Frye didn’t go there, but Ali ruined some part of the great athlete Michael Jordan for me. Years ago, at the height of his popularity and given a chance to support Harvey Gantt, the black progressive mayor of Charlotte, N.C., against that old racemonger Senator Jesse Helms, Jordan declined. Republicans, he reportedly said, buy sneakers too.

Others spoke and acted in the Ali tradition. Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists in the black-power sign at the Olympics in 1968 after medaling in the 200-meter race. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar has spoken out often and thoughtfully on society’s ills. LeBron James has addressed violence and police brutality, and is a union activist. The cross-country skier Beckie Scott has spoken out repeatedly on athletic doping and on the fecklessness of international organizations.

The point is not whether you agree with their every utterance, any more than that was so with regard to Ali. To see athletes — young men and women who could rightly enough claim obsession with sport and endorsements — embrace the larger world and its discontents is moving.Ali was a man, which is to say complicated and many-faced and imperfect. He could be cruel to opponents, in the ring and outside it. Joe Frazier, he said, was too dumb and too ugly to be champion.

It is probably smart not to get too worked up about this. Cruelty is woven into boxing like tweed into a fine herringbone jacket.

Ali reincarnated himself as champion, three times winning that title, and that gave to his life narrative a metaphorical power.

I know the young Ali, lean and dangerous and endlessly boastful, only through my father’s stories, and from old newsreels. The Ali I remember was heavier-muscled and a ferocious competitor, too willing to stand and absorb punishment. By the time he tangled with George Foreman in 1974 in Zaire, the fight known as the Rumble in the Jungle, his speed and reflexes were like bike tires worn down.

The question was not whether Foreman would beat him senseless, but how quickly the end would come.

Ali, per usual, would have none of that. “If you think the world was surprised when Nixon resigned, wait till I whup Foreman’s behind,” he told David Frost.

Here’s Norman Mailer’s classic account in the “The Fight.” Ali would “slide off a punch and fall back into the ropes with all the calm of a man swinging in the rigging. All the while, he used his eyes. They looked like stars, and he feinted Foreman out with his eyes, flashing white eyeballs of panic he did not feel which pulled Foreman through into the trick of lurching after him on a wrong move.”

I drove back to Purchase College that night and listened to the staccato, round-by-round reports on WINS news radio. When the anchor broke in excitedly to say that Ali had toppled Foreman in the eighth round like an oak tree, I pounded my dashboard and screamed like a banshee loose on the Hutchinson River Parkway.

Ali’s decline would play no small part in my own decision to turn away from boxing. I had read of Joe Louis, slowed and thick-tongued and lost late in his life. But unlike my parents, I never knew him in his thunderbolt-throwing prime. Ali was the athlete of my youth. By the end, Parkinson’s and his past braveries in the ring had rendered Ali near immobile and mute.

Now he is dead.

Here is another outtake from that primal force. He had listened as young white men berated him for resisting the draft. Then, eyes flashing, he came back at them.

“You talking about me about some draft and all you white boys are breaking your neck to get to Switzerland and Canada and London,” he said, adding, “If I’m going to die, I’ll die now right here, fighting you.”

The words speak to a passion forever young, and brave.

*****

At first, he was just a commotion, far down State Street.

Muhammad Ali was usually a commotion in those days.

Then he materialized, followed by a raggle-taggle army, Muhammad Ali’s irregulars, your basic rainbow coalition of the late 1960s, falling in step behind him, chanting: “Muhammad Ali is our champ! Muhammad Ali is our champ!”

This was Chicago, circa 1968, while Ali was suspended for refusing to enter the military draft, uttering the famous line, “I ain’t got no quarrel against them Vietcong.”

I remember it as a sunny midday in Chicago, one of his cities — heck, a lot of cities were his in those heightened times — and perhaps the Champ was just out for a stroll, as I was, a young baseball writer in town with the Yanks, or maybe it was the Mets.

I had never seen Ali in person, but geez he was beautiful, big and limber and smiling, and it didn’t look like he had much else to do but walk down State Street, collecting black people and white people and brown people and young people and old people, surely not everybody in America, for he was a draft dodger and a Muslim and whatever else you wanted to call him, but he was the champion of State Street that day, the once and future champ.

That was Ali in America in the late ’60s, a lot of things wrapped up in one graceful, complicated package.

Later I got to watch him fall apart, and know him just a little bit, and once I jogged with him for, oh, maybe half a mile. These stories come back to me as I mourn Muhammad Ali.

The first time I got to report on Ali, as best I can remember, was in 1974 after he beat George Foreman in Zaire and came back home to Louisville, Ky. By now, I was a news reporter who had lived in Kentucky for a while — more familiar with coal mining’s human toll than boxing’s — and The New York Times asked me to cover Ali’s homecoming.

They introduced him at dusk in the big plaza alongside the Ohio River as whites and blacks celebrated him, the actual champ again. As always, he was a master at manipulating the crowd. He stood on a stage and towered over a tiny black man who looked to be about 12 years old. Ali saw the humor in this and asked if anybody knew who this little brother was, asLouisville’s mayor, Harvey Sloane, seemed to fret about where this was all going.

Ali told the crowd who the little man was — Galenge Mbangu, 22, the pilot of the Air Zaire DC-10 that had flown Ali before he came home with his championship belt.

Ali told the crowd who the little man was — Galenge Mbangu, 22, the pilot of the Air Zaire DC-10 that had flown Ali before he came home with his championship belt.

“He didn’t have no blond hair and blue eyes, but we made it anyway,” Ali told the crowd, like it was still the ’60s and there were lessons to be taught.

He wasn’t so beautiful by the time I went back to sports in 1980 because he had taken a lot of punches. He trudged slowly, with some dignity and some tremors, as he prepared to fight Larry Holmes in Las Vegas, and I got to meet some of his people, like his photographer, Howard Bingham, one of the truly sweet people, and Ali’s lippy cheerleader, Drew (Bundini) Brown, who had invented the phrase, “Float like a butterfly! Sting like a bee!” Ali got beat up by Holmes, an ugly sight. It was the first time I saw him fight.

His next fight was Trevor Berbick in the Bahamas. I was sent down to cover it, and wangled a chance to jog with Ali in the traditional predawn training regimen. Always before dawn. I was a five-mile runner in those days, and looked forward to jogging alongside the champ, who was meek and sweet now, no trace of the vitriol that Floyd Patterson and Joe Frazier had felt so viscerally.

Muhammad Ali’s Words Stung Like a Bee, Too

Outside the boxing ring, Ali fought his battles with his mouth.

We shuffled out into the darkness for a minute or so, and I hadn’t broken a sweat yet, and Ali whispered hoarsely to nobody in particular, “Let’s go back.” So we went back to the training camp and he did magic tricks, as a good Muslim, following the Quran’s position about magic, explaining each trick. That was how Ali spent many hours of training.

My wife flew down a few days before the fight. The camp was highly informal, and by now, I knew everybody in the entourage. Boxing is like that. I ushered my wife into the midday alleged sparring session and was told the champ was resting on the training table, so I ushered her to the inner sanctum where Ali looked like an ancient African prince on his deathbed.

“Champ,” I said, “I’d like you to meet my wife,” and he whispered something, with barely enough energy to speak, and I motioned for Marianne to move closer, and he said something to her, and she laughed, very sweetly. What he said was, “You can do better.” (People told me it was his stock line. No matter. She was charmed. Plus, he was probably right.)

“Champ,” I said, “I’d like you to meet my wife,” and he whispered something, with barely enough energy to speak, and I motioned for Marianne to move closer, and he said something to her, and she laughed, very sweetly. What he said was, “You can do better.” (People told me it was his stock line. No matter. She was charmed. Plus, he was probably right.)

So that was Ali, the people’s champ, and he got beat up by Berbick and never fought again, and the rest of his life was a testimony to the destructive force of boxing, a sport I would abolish if I could. But then again, boxing gave us Ali and his counterpart, Smokin’ Joe Frazier, quivering with anger for the rest of his life at the way Ali called him a gorilla.

They were America, as much as anybody — race playing out between two boxers, one from a Gullah section of South Carolina, one with white roots from Kentucky.

The Champ lived a long time after that, three and a half decades, many things to many people. I would see him at banquets or sports events, escorted by his lovely wife, Lonnie. He was in there, whispering to people he knew well – Dick Schaap, Howard Cosell, Dave Anderson, Bingham — the mother wit, the intelligence that no I.Q. test could ever measure. In his later decades, he was a gentle soul, courtesy of boxing’s ravages.

He was America’s broken prince, one of our princes, anyway, and when I saw him shuffling, I always remembered the erect beautiful prince striding down State Street as the crowd chanted, yes: “Muhammad Ali is our champ! Muhammad Ali is our champ!”

*****

Muhammad Ali (/ɑːˈliː/;[5] born Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr., January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer. Early in his career, Ali was known for being an inspiring, controversial and polarizing figure both inside and outside the boxing ring.[6][7]

Clay was born in Louisville, Kentucky, and he began training when he was 12 years old. At 22, he won the world heavyweight championship from Sonny Liston in an upset in 1964. Shortly after that, Clay converted to Islam, changed his "slave" name to Ali, and gave a message of racial pride for African Americans and resistance to white domination.[8][9]

In 1966, two years after winning the heavyweight title, Ali further antagonized the white establishment by refusing to be conscripted into the U.S. military, citing his religious beliefs and opposition to American involvement in the Vietnam War.[8] He was eventually arrested and found guilty of draft evasion charges and stripped of his boxing titles, which he successfully appealed in the U.S. Supreme Court where, in 1971, his conviction was overturned. Due to this hiatus, he had not fought again for nearly four years—losing a time of peak performance as an athlete. Ali's actions as a conscientious objector to the war made him an icon for the larger counterculture generation.[10][11]

Ali remains the only three-time lineal world heavyweight champion; he won the title in 1964, 1974, and 1978. Between February 25, 1964, and September 19, 1964, Ali reigned as the heavyweight boxing champion. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he was involved in several historic boxing matches.[12] Notable among these were the first Liston fight, three with rival Joe Frazier, and "The Rumble in the Jungle" withGeorge Foreman, in which he regained titles he had been stripped of seven years earlier.

At a time when most fighters let their managers do the talking, Ali, inspired by professional wrestler "Gorgeous George" Wagner, thrived in—and indeed craved—the spotlight, where he was often provocative and outlandish.[13][14][15]

Ancestry, early life, and amateur career

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. was born on January 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky.[16] He had a sister and four brothers, including Nathaniel Clay.[17][18] He was named for his father, Cassius Marcellus Clay Sr., who himself was named in honor of the 19th-century Republican politician and staunch abolitionist, Cassius Marcellus Clay, also from the state of Kentucky. Clay's paternal grandparents were John Clay and Sallie Anne Clay; Clay's sister Eva claimed that Sallie was a native of Madagascar.[19] He was a descendant of pre-civil war era American slaves in the American South, and was predominantly of African descent, with Irish[20] and English heritage.[21][22][23] His father painted billboards and signs,[16] and his mother, Odessa O'Grady Clay, was a household domestic. Although Cassius Sr. was a Methodist, he allowed Odessa to bring up both Cassius and his younger brother Rudolph "Rudy" Clay (later renamed Rahman Ali) as Baptists.[24] He grew up in racial segregation with his mother recalling one occasion where he was denied a drink of water at a store, "they wouldn't give him one because of his color. That really affected him."[8]

He was first directed toward boxing by Louisville police officer and boxing coach Joe E. Martin,[25] who encountered the 12-year-old fuming over a thief taking his bicycle. He told the officer he was going to "whup" the thief. The officer told him he had better learn how to box first.[26]For the last four years of Clay's amateur career he was trained by boxing cutman Chuck Bodak.[27]

Clay made his amateur boxing debut in 1954.[28] He won six Kentucky Golden Gloves titles, two national Golden Gloves titles, an Amateur Athletic Union national title, and the Light Heavyweight gold medal in the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome.[29] Clay's amateur record was 100 wins with five losses. Ali claimed in his 1975 autobiography that shortly after his return from the Rome Olympics he threw his gold medal into the Ohio River after he and a friend were refused service at a "whites-only" restaurant and fought with a white gang. The story has since been disputed and several of Ali's friends, including Bundini Brown and photographer Howard Bingham, have denied it. Brown told Sports Illustrated writer Mark Kram, "Honkies sure bought into that one!" Thomas Hauser's biography of Ali stated that Ali was refused service at the diner but that he lost his medal a year after he won it.[30] Ali received a replacement medal at a basketball intermission during the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, where he lit the torch to start the games.

Professional boxing

Early career

Clay made his professional debut on October 29, 1960, winning a six-round decision over Tunney Hunsaker. From then until the end of 1963, Clay amassed a record of 19–0 with 15 wins by knockout. He defeated boxers including Tony Esperti, Jim Robinson, Donnie Fleeman, Alonzo Johnson, George Logan, Willi Besmanoff, Lamar Clark, Doug Jones and Henry Cooper. Clay also beat his former trainer and veteran boxer Archie Moore in a 1962 match.

These early fights were not without trials. Clay was knocked down both by Sonny Banks and Cooper. In the Cooper fight, Clay was floored by a left hook at the end of round four and was saved by the bell. The fight with Doug Jones on March 13, 1963, was Clay's toughest fight during this stretch. The number-two and -three heavyweight contenders respectively, Clay and Jones fought on Jones' home turf at New York's Madison Square Garden. Jones staggered Clay in the first round, and the unanimous decision for Clay was greeted by boos and a rain of debris thrown into the ring (watching on closed-circuit TV, heavyweight champ Sonny Liston quipped that if he fought Clay he might get locked up for murder). The fight was later named "Fight of the Year".

In each of these fights, Clay vocally belittled his opponents and vaunted his abilities. Jones was "an ugly little man" and Cooper was a "bum". He was embarrassed to get in the ring with Alex Miteff. Madison Square Garden was "too small for me".[31] Clay's behavior provoked the ire of many boxing fans.[32]

After Clay left Moore's camp in 1960, partially due to Clay's refusing to do chores such as dish-washing and sweeping, he hired Angelo Dundee, whom he had met in February 1957 during Ali's amateur career,[33] to be his trainer. Around this time, Clay sought longtime idol Sugar Ray Robinson to be his manager, but was rebuffed.[34]

Heavyweight champion

Further information: Muhammad Ali vs. Sonny Liston

By late 1963, Clay had become the top contender for Sonny Liston's title. The fight was set for February 25, 1964, in Miami. Liston was an intimidating personality, a dominating fighter with a criminal past and ties to the mob. Based on Clay's uninspired performance against Jones and Cooper in his previous two fights, and Liston's destruction of former heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson in two first-round knock outs, Clay was a 7–1 underdog. Despite this, Clay taunted Liston during the pre-fight buildup, dubbing him "the big ugly bear". "Liston even smells like a bear", Clay said. "After I beat him I'm going to donate him to the zoo."[35] Clay turned the pre-fight weigh-in into a circus, shouting at Liston that "someone is going to die at ringside tonight". Clay's pulse rate was measured at 120, more than double his normal 54.[36] Many of those in attendance thought Clay's behavior stemmed from fear, and some commentators wondered if he would show up for the bout.

The outcome of the fight was a major upset. At the opening bell, Liston rushed at Clay, seemingly angry and looking for a quick knockout, but Clay's superior speed and mobility enabled him to elude Liston, making the champion miss and look awkward. At the end of the first round Clay opened up his attack and hit Liston repeatedly with jabs. Liston fought better in round two, but at the beginning of the third round Clay hit Liston with a combination that buckled his knees and opened a cut under his left eye. This was the first time Liston had ever been cut. At the end of round four, as Clay returned to his corner, he began experiencing blinding pain in his eyes and asked his trainer Angelo Dundee to cut off his gloves. Dundee refused. It has been speculated that the problem was due to ointment used to seal Liston's cuts, perhaps deliberately applied by his corner to his gloves.[36] Though unconfirmed, Bert Sugar claimed that two of Liston's opponents also complained about their eyes "burning".[37][38]

Despite Liston's attempts to knock out a blinded Clay, Clay was able to survive the fifth round until sweat and tears rinsed the irritation from his eyes. In the sixth, Clay dominated, hitting Liston repeatedly. Liston did not answer the bell for the seventh round, and Clay was declared the winner by TKO. Liston stated that the reason he quit was an injured shoulder. Following the win, a triumphant Clay rushed to the edge of the ring and, pointing to the ringside press, shouted: "Eat your words!" He added, "I am the greatest! I shook up the world. I'm the prettiest thing that ever lived."[39]

In winning this fight, Clay became at age 22 the youngest boxer to take the title from a reigning heavyweight champion, though Floyd Patterson was the youngest to win the heavyweight championship at 21, during an elimination bout following Rocky Marciano's retirement. Mike Tyson broke both records in 1986 when he defeated Trevor Berbick to win the heavyweight title at age 20.

Soon after the Liston fight, Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali upon converting to Islam and affiliating with the Nation of Islam. Ali then faced a rematch with Liston scheduled for May 1965 in Lewiston, Maine. It had been scheduled for Boston the previous November, but was postponed for six months due to Ali's emergency surgery for a hernia three days before.[40] The fight was controversial. Midway through the first round, Liston was knocked down by a difficult-to-see blow the press dubbed a "phantom punch". Ali refused to retreat to a neutral corner, and referee Jersey Joe Walcott did not begin the count. Liston rose after he had been down about 20 seconds, and the fight momentarily continued. But a few seconds later Walcott stopped the match, declaring Ali the winner by knockout. The entire fight lasted less than two minutes.[41]

It has since been speculated that Liston dropped to the ground purposely. Proposed motivations include threats on his life from the Nation of Islam, that he had bet against himself and that he "took a dive" to pay off debts. Slow-motion replays show that Liston was jarred by a chopping right from Ali, although it is unclear whether the blow was a genuine knock-out punch.[42]

Ali defended his title against former heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson on November 22, 1965. Before the match, Ali mocked Patterson, who was widely known to call him by his former name Cassius Clay, as an "Uncle Tom", calling him "The Rabbit". Although Ali clearly had the better of Patterson, who appeared injured during the fight, the match lasted 12 rounds before being called on a technical knockout. Patterson later said he had strained his sacroiliac. Ali was criticized in the sports media for appearing to have toyed with Patterson during the fight.[43]

Ali and then-WBA heavyweight champion boxer Ernie Terrell had agreed to meet for a bout in Chicago on March 29, 1966 (the WBA, one of two boxing associations, had stripped Ali of his title following his joining the Nation of Islam). But in February Ali was reclassified by the Louisville draft board as 1-A from 1-Y, and he indicated that he would refuse to serve, commenting to the press, "I ain't got nothing against no Viet Cong; no Viet Cong never called me nigger."[44] Amidst the media and public outcry over Ali's stance, the Illinois Athletic Commission refused to sanction the fight, citing technicalities.[45]

Instead, Ali traveled to Canada and Europe and won championship bouts against George Chuvalo, Henry Cooper, Brian London and Karl Mildenberger.

Ali returned to the United States to fight Cleveland Williams in the Houston Astrodome on November 14, 1966. The bout drew a record-breaking indoor crowd of 35,460 people. Williams had once been considered among the hardest punchers in the heavyweight division, but in 1964 he had been shot at point-blank range by a Texas policeman, resulting in the loss of one kidney and 10 feet (3.0 m) of his small intestine. Ali dominated Williams, winning a third-round technical knockout in what some consider the finest performance of his career.

Ali fought Terrell in Houston on February 6, 1967. Terrell was billed as Ali's toughest opponent since Liston—unbeaten in five years and having defeated many of the boxers Ali had faced. Terrell was big, strong and had a three-inch reach advantage over Ali. During the lead up to the bout, Terrell repeatedly called Ali "Clay", much to Ali's annoyance (Ali called Cassius Clay his "slave name"). The two almost came to blows over the name issue in a pre-fight interview with Howard Cosell. Ali seemed intent on humiliating Terrell. "I want to torture him", he said. "A clean knockout is too good for him."[46] The fight was close until the seventh round when Ali bloodied Terrell and almost knocked him out. In the eighth round, Ali taunted Terrell, hitting him with jabs and shouting between punches, "What's my name, Uncle Tom... what's my name?" Ali won a unanimous 15-round decision. Terrell claimed that early in the fight Ali deliberately thumbed him in the eye—forcing Terrell to fight half-blind—and then, in a clinch, rubbed the wounded eye against the ropes. Because of Ali's apparent intent to prolong the fight to inflict maximum punishment, critics described the bout as "one of the ugliest boxing fights". Tex Maule later wrote: "It was a wonderful demonstration of boxing skill and a barbarous display of cruelty." Ali denied the accusations of cruelty but, for Ali's critics, the fight provided more evidence of his arrogance.

After Ali's title defense against Zora Folley on March 22, he was stripped of his title due to his refusal to be drafted to army service.[16] His boxing license was also suspended by the state of New York. He was convicted of draft evasion on June 20 and sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. He paid a bond and remained free while the verdict was being appealed.

Exile and comeback

Main articles: Fight of the Century and Muhammad Ali vs. Joe Frazier II

In March of 1966, Ali refused to be inducted into the armed forces, stating that he had "no quarrel with them Vietcong".[47] "My conscience won't let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America. And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn't put no dogs on me, they didn't rob me of my nationality, rape or kill my mother and father.... How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail."[48] He was systematically denied a boxing license in every state and stripped of his passport. As a result, he did not fight from March 1967 to October 1970—from ages 25 to almost 29—as his case worked its way through the appeals process. In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his conviction in a unanimous 8–0 ruling (Thurgood Marshall recused himself, as he had been the U.S. Solicitor General at the time of Ali's conviction).

During this time of inactivity, as opposition to the Vietnam War began to grow and Ali's stance gained sympathy, he spoke at colleges across the nation, criticizing the Vietnam War and advocating African American pride and racial justice.

On August 12, 1970, with his case still in appeal, Ali was granted a license to box by the City of Atlanta Athletic Commission, thanks to State Senator Leroy R. Johnson.[49] Ali's first return bout was against Jerry Quarry on October 26, resulting in a win after three rounds after Quarry was cut.

A month earlier, a victory in federal court forced the New York State Boxing Commission to reinstate Ali's license.[50] He fought Oscar Bonavena at Madison Square Garden in December, an uninspired performance that ended in a dramatic TKO of Bonavena in the 15th round. The win left Ali as a top contender against heavyweight champion Joe Frazier.

Ali and Frazier's first fight, held at the Garden on March 8, 1971, was nicknamed the "Fight of the Century", due to the tremendous excitement surrounding a bout between two undefeated fighters, each with a legitimate claim as heavyweight champions. Veteran boxing writer John Condon called it "the greatest event I've ever worked on in my life". The bout was broadcast to 35 foreign countries; promoters granted 760 press passes.[30]

Adding to the atmosphere were the considerable pre-fight theatrics and name calling. Ali portrayed Frazier as a "dumb tool of the white establishment". "Frazier is too ugly to be champ", Ali said. "Frazier is too dumb to be champ." Ali also frequently called Frazier an Uncle Tom. Dave Wolf, who worked in Frazier's camp, recalled that, "Ali was saying 'the only people rooting for Joe Frazier are white people in suits, Alabama sheriffs, and members of the Ku Klux Klan. I'm fighting for the little man in the ghetto.' Joe was sitting there, smashing his fist into the palm of his hand, saying, 'What the fuck does he know about the ghetto?'"[30]

Ali began training at a farm near Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1971 and, finding the country setting to his liking, sought to develop a real training camp in the countryside. He found a five-acre site on a Pennsylvania country road in the village of Deer Lake, On this site, Ali carved out what was to become his training camp, the camp where he lived and trained for all the many fights he had from 1972 on to the end of his career in the 1980s.

The Monday night fight lived up to its billing. In a preview of their two other fights, a crouching, bobbing and weaving Frazier constantly pressured Ali, getting hit regularly by Ali jabs and combinations, but relentlessly attacking and scoring repeatedly, especially to Ali's body. The fight was even in the early rounds, but Ali was taking more punishment than ever in his career. On several occasions in the early rounds he played to the crowd and shook his head "no" after he was hit. In the later rounds—in what was the first appearance of the "rope-a-dope strategy"—Ali leaned against the ropes and absorbed punishment from Frazier, hoping to tire him. In the 11th round, Frazier connected with a left hook that wobbled Ali, but because it appeared that Ali might be clowning as he staggered backwards across the ring, Frazier hesitated to press his advantage, fearing an Ali counter-attack. In the final round, Frazier knocked Ali down with a vicious left hook, which referee Arthur Mercante said was as hard as a man can be hit. Ali was back on his feet in three seconds.[30] Nevertheless, Ali lost by unanimous decision, his first professional defeat.

Ali's characterizations of Frazier during the lead-up to the fight cemented a personal animosity toward Ali by Frazier that lasted until Frazier's death.[30] Frazier and his camp always considered Ali's words cruel and unfair, far beyond what was necessary to sell tickets. Shortly after the bout, in the TV studios of ABC's Wide World of Sports during a nationally televised interview with the two boxers, Frazier rose from his chair and wrestled Ali to the floor after Ali called him ignorant.

In the same year basketball star Wilt Chamberlain challenged Ali, and a fight was scheduled for July 26. Although the seven foot two inch tall Chamberlain had formidable physical advantages over Ali, weighing 60 pounds more and able to reach 14 inches further, Ali was able to intimidate Chamberlain into calling off the bout. This happened during a shared press conference with Chamberlain in which Ali repeatedly responded to reporters with the traditional lumberjack warning, "Timber", and said, "The tree will fall!" With these statements of confidence, Ali was able to unsettle his taller opponent into calling off the bout.[51]

After the loss to Frazier, Ali fought Jerry Quarry, had a second bout with Floyd Patterson and faced Bob Foster in 1972, winning a total of six fights that year. In 1973, Ken Norton broke Ali's jaw while giving him the second loss of his career. After initially seeking retirement, Ali won a controversial decision against Norton in their second bout, leading to a rematch at Madison Square Garden on January 28, 1974, with Joe Frazier who had recently lost his title to George Foreman.

Ali was strong in the early rounds of the fight, and staggered Frazier in the second round (referee Tony Perez mistakenly thought he heard the bell ending the round and stepped between the two fighters as Ali was pressing his attack, giving Frazier time to recover). However, Frazier came on in the middle rounds, snapping Ali's head in round seven and driving him to the ropes at the end of round eight. The last four rounds saw round-to-round shifts in momentum between the two fighters. Throughout most of the bout, however, Ali was able to circle away from Frazier's dangerous left hook and to tie Frazier up when he was cornered, the latter a tactic that Frazier's camp complained of bitterly. Judges awarded Ali a unanimous decision.

Heavyweight champion (second tenure)

Main articles: The Rumble in the Jungle and Thrilla in Manila

The defeat of Frazier set the stage for a title fight against heavyweight champion George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire, on October 30, 1974 — a bout nicknamed "The Rumble in the Jungle". Foreman was considered one of the hardest punchers in heavyweight history. In assessing the fight, analysts pointed out that Joe Frazier and Ken Norton — who had given Ali four tough battles and won two of them—had been both devastated by Foreman in second round knockouts. Ali was 32 years old, and had clearly lost speed and reflexes since his twenties. Contrary to his later persona, Foreman was at the time a brooding and intimidating presence. Almost no one associated with the sport, not even Ali's long-time supporterHoward Cosell, gave the former champion a chance of winning.

As usual, Ali was confident and colorful before the fight. He told interviewer David Frost, "If you think the world was surprised when Nixon resigned, wait 'til I whup Foreman's behind!"[52]He told the press, "I've done something new for this fight. I done wrestled with an alligator, I done tussled with a whale; handcuffed lightning, thrown thunder in jail; only last week, I murdered a rock, injured a stone, hospitalized a brick; I'm so mean I make medicine sick."[53] Ali was wildly popular in Zaire, with crowds chanting "Ali, bomaye" ("Ali, kill him") wherever he went.

Ali opened the fight moving and scoring with right crosses to Foreman's head. Then, beginning in the second round—and to the consternation of his corner—Ali retreated to the ropes and invited Foreman to hit him while covering up, clinching and counter-punching, all while verbally taunting Foreman. ("Is that all you got, George? They told me you could hit.") The move, which would later become known as the "Rope-A-Dope", so violated conventional boxing wisdom—letting one of the hardest hitters in boxing strike at will—that at ringside writer George Plimpton thought the fight had to be fixed.[30] Foreman, increasingly angered, threw punches that were deflected and did not land squarely. Midway through the fight, as Foreman began tiring, Ali countered more frequently and effectively with punches and flurries, which electrified the pro-Ali crowd. In the eighth round, Ali dropped an exhausted Foreman with a combination at center ring; Foreman failed to make the count. Against the odds, and amidst pandemonium in the ring, Ali had regained the title by knockout.

In reflecting on the fight, George Foreman later said: "I'll admit it. Muhammad outthought me and outfought me."[30]

Ali's next opponents included Chuck Wepner, Ron Lyle, and Joe Bugner. Wepner, a journeyman known as "The Bayonne Bleeder", stunned Ali with a knockdown in the ninth round; Ali would later say he tripped on Wepner's foot. It was a bout that would inspire Sylvester Stallone to create the acclaimed film, Rocky.

Ali then agreed to a third match with Joe Frazier in Manila. The bout, known as the "Thrilla in Manila", was held on October 1, 1975,[16] in temperatures approaching 100 °F (38 °C). In the first rounds, Ali was aggressive, moving and exchanging blows with Frazier. However, Ali soon appeared to tire and adopted the "rope-a-dope" strategy, frequently resorting to clinches. During this part of the bout Ali did some effective counter-punching, but for the most part absorbed punishment from a relentlessly attacking Frazier. In the 12th round, Frazier began to tire, and Ali scored several sharp blows that closed Frazier's left eye and opened a cut over his right eye. With Frazier's vision now diminished, Ali dominated the 13th and 14th rounds, at times conducting what boxing historian Mike Silver called "target practice" on Frazier's head. The fight was stopped when Frazier's trainer, Eddie Futch, refused to allow Frazier to answer the bell for the 15th and final round, despite Frazier's protests. Frazier's eyes were both swollen shut. Ali, in his corner, winner by TKO, slumped on his stool, clearly spent.

An ailing Ali said afterwards that the fight "was the closest thing to dying that I know", and, when later asked if he had viewed the fight on videotape, reportedly said, "Why would I want to go back and see Hell?" After the fight he cited Frazier as "the greatest fighter of all times next to me".

Decline

Following the Manila bout, Ali fought Jean-Pierre Coopman, Jimmy Young, and Richard Dunn, winning the last by knockout. Later in 1976, he participated in an exhibition bout in Tokyo against Japanese professional wrestler and martial artist Antonio Inoki(Muhammad Ali vs. Antonio Inoki).[54] Though the fight was a publicity stunt, Inoki's kicks caused bruises, two blood clots and an infection in Ali's legs.[54] The fight was ultimately declared a draw.[54] He fought Ken Norton for the third time at Yankee Stadium in September 1976, where Ali won by a heavily contested decision, which was loudly booed by the audience. Afterwards, he announced he was retiring from boxing to practice his faith, having converted to Sunni Islam after falling out with the NOI the previous year.[55]

After winning against Alfredo Evangelista in May 1977, Ali struggled in his next fight against Earnie Shavers that September, who pummeled him a few times with punches to the head. Ali won the fight by another unanimous decision, but the bout caused his longtime doctor Ferdie Pacheco to quit after he was rebuffed for telling Ali he should retire. Pacheco was quoted as saying, "the New York State Athletic Commission gave me a report that showed Ali's kidneys were falling apart. I wrote to Angelo Dundee, Ali's trainer, his wife and Ali himself. I got nothing back in response. That's when I decided enough is enough."[30]

In February 1978, Ali faced Leon Spinks at the Hilton Hotel in Las Vegas. At the time, Spinks had only seven professional fights to his credit, and had recently fought a draw with journeyman Scott LeDoux. Ali sparred less than two dozen rounds in preparation for the fight, and was seriously out of shape by the opening bell. He lost the title by split decision. A rematch followed shortly thereafter in New Orleans, which broke attendance records. Ali won a unanimous decision in an uninspiring fight, making him the first heavyweight champion to win the belt three times.[56]

Following this win, on July 27, 1979, Ali announced his retirement from boxing. His retirement was short-lived, however; Ali announced his comeback to face Larry Holmes for the WBC belt in an attempt to win the heavyweight championship an unprecedented fourth time. The fight was largely motivated by Ali's need for money. Boxing writer Richie Giachetti said, "Larry didn't want to fight Ali. He knew Ali had nothing left; he knew it would be a horror."

It was around this time that Ali started struggling with vocal stutters and trembling hands.[57] The Nevada Athletic Commission (NAC) ordered that he undergo a complete physical in Las Vegas before being allowed to fight again. Ali chose instead to check into the Mayo Clinic, who declared him fit to fight. Their opinion was accepted by the NAC on July 31, 1980, paving the way for Ali's return to the ring.[58]

The fight took place on October 2, 1980, in Las Vegas, with Holmes easily dominating Ali, who was weakened from thyroid medication he had taken to lose weight. Giachetti called the fight "awful... the worst sports event I ever had to cover". ActorSylvester Stallone at ringside said it was like watching an autopsy on a man who is still alive.[30] Ali's trainer Angelo Dundee finally stopped the fight in the eleventh round, the only fight Ali lost by knockout. The Holmes fight is said to have contributed to Ali's Parkinson's syndrome.[59] Despite pleas to definitively retire, Ali fought one last time on December 11, 1981 in Nassauagainst Trevor Berbick, losing a ten-round decision.[60][61][62]

Later years

On January 19, 1981, in Los Angeles, Ali talked a man down from jumping off a ninth-floor ledge, an event that made national news.[63][64]

Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson's syndrome in 1984, a disease that sometimes results from head trauma from activities such as boxing.[65][66][67] Ali still remained active during this time, however, later participating as a guest referee at WrestleMania I.[68][69]

In 1984, Ali announced his support for the reelection of United States President Ronald Reagan, when asked to elaborate on his endorsement of Reagan, Ali told reporters, "He's keeping God in schools and that's enough."[70]

Around 1987, the California Bicentennial Foundation for the U.S. Constitution selected Ali to personify the vitality of the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights. Ali rode on a float at the following year's Tournament of Roses Parade, launching the U.S. Constitution's 200th birthday commemoration.

Ali published an oral history, Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times by Thomas Hauser, in 1991. That same year, Ali traveled to Iraq during the Gulf War, and met with Saddam Hussein in an attempt to negotiate the release of American hostages.[71] In 1996, he had the honor of lighting the flame at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia.

Ali's bout with Parkinson's led to a gradual decline in Ali's health though he was still active into the early years of the millennium, even promoting his own biopic, Ali, in 2001. Ali also contributed an on-camera segment to the America: A Tribute to Heroes benefit concert.

On November 17, 2002, Muhammad Ali went to Afghanistan as the "U.N. Messenger of Peace".[72] He was in Kabul for a three-day goodwill mission as a special guest of the UN.[73]

On September 1, 2009, Ali visited Ennis, County Clare, Ireland, the home of his great-grandfather, Abe Grady, who emigrated to the U.S. in the 1860s, eventually settling in Kentucky.[74] A crowd of 10,000 turned out for a civic reception, where Ali was made the first Honorary Freeman of Ennis.[75]

On July 27, 2012, Ali was a titular bearer of the Olympic Flag during the opening ceremonies of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London. He was helped to his feet by his wife Lonnie to stand before the flag due to his Parkinson's rendering him unable to carry it into the stadium.[76]

Health issues and death

In February 2013, Ali's brother, Rahman Ali, said Muhammad could no longer speak and could be dead within days.[77] Ali's daughter, May May Ali, responded to the rumors, stating that she had talked to him on the phone the morning of February 3 and he was fine.[78]

On December 20, 2014, Ali was hospitalized for a mild case of pneumonia.[79] Ali was once again hospitalized on January 15, 2015, for a urinary tract infection after being found unresponsive at a guest house in Scottsdale, Arizona.[80][81] He was released the next day.[82]

Ali was hospitalized in Scottsdale in June 2016, with a respiratory illness. Though his condition was initially described as "fair", his condition worsened and he died the following day aged 74. His death was attributed to septic shock.[83][84][85][86]

Personal life

Marriages and children

Ali was married four times and had seven daughters and two sons. Ali met his first wife, cocktail waitress Sonji Roi, approximately one month before they married on August 14, 1964.[87] Roi's objections to certain Muslim customs in regard to dress for women contributed to the breakup of their marriage. They divorced on January 10, 1966.

On August 17, 1967, Ali married Belinda Boyd. After the wedding, she, like Ali, converted to Islam. She changed her name to Khalilah Ali, though she was still called Belinda by old friends and family. They had four children: Maryum (born 1968), twins Jamillah and Rasheda (born 1970), and Muhammad Ali, Jr. (born 1972).[88] Maryum has a career as an author and rapper.[89]

In 1975, Ali began an affair with Veronica Porsche, an actress and model. By the summer of 1977, his second marriage was over and he had married Porsche.[citation needed] At the time of their marriage, they had a baby girl, Hana, and Veronica was pregnant with their second child. Their second daughter, Laila Ali, was born in December 1977. By 1986, Ali and Porsche were divorced.[citation needed]

Laila became a boxer in 1999,[90] despite her father's earlier comments against female boxing in 1978: "Women are not made to be hit in the breast, and face like that... the body's not made to be punched right here [patting his chest]. Get hit in the breast... hard... and all that."[91]

On November 19, 1986, Ali married Yolanda ("Lonnie") Williams. They had been friends since 1964 in Louisville. They have one son, Asaad Amin, whom they adopted when Amin was five months old.[88][92][93][94][95]

Ali was a resident of Cherry Hill, New Jersey, in the early 1970s.[96] He had two other daughters, Miya and Khaliah, from extramarital relationships.[88][97]

Ali most recently lived in Scottsdale, Arizona, with Lonnie.[98] In January 2007 it was reported that they had put their home inBerrien Springs, up for sale and had purchased a home in eastern Jefferson County, Kentucky, for $1,875,000.[99] Lonnie converted to Islam from Catholicism in her late twenties.[100]

Through Hana, Ali's son-in-law is mixed martial artist Kevin Casey.[101]

Religion and beliefs

Affiliation with the Nation of Islam

Ali said that he first heard of the Nation of Islam (NOI) when he was fighting in the Golden Gloves tournament in Chicago in 1959, and attended his first NOI meeting in 1961. He continued to attend meetings, although keeping his involvement hidden from the public. In 1962, Clay met Malcolm X, who soon became his spiritual and political mentor, and by the time of the first Liston fight NOI members, including Malcolm X, were visible in his entourage. This led to a story in The Miami Herald just before the fight disclosing that Clay had joined the Nation, which nearly caused the bout to be canceled.

In fact, Clay was initially refused entry to the Nation of Islam (often called the Black Muslims at the time) due to his boxing career.[102] However, after he won the championship from Liston in 1964, the Nation of Islam was more receptive and agreed to recruit him as a member.[102] Shortly afterwards, Elijah Muhammad recorded a statement that Clay would be renamed Muhammad (one who is worthy of praise) Ali(Ali is the most important figure after Muhammad in Shia view and fourth rightly guided caliph in Sunni view). Around that time Ali moved to the South Side of Chicago and lived in a series of houses, always near the NOI's Mosque Maryam or Elijah Muhammad's residence. He stayed in Chicago for about 12 years.[103]